Wednesday, January 17, 2007

Blair gets hot under the collar

Shackley, S, Young, P, Parkinson, S & Wynne, B (1998) Uncertainty, Complexity and Concepts of Good Science in Climate change: Are GCMs The Best Tools? Climate Change 38: 159-205

Ryan questions the wisdom of predicting additional diarrhoea deaths from climate change given uncertainties in “unstable government, a fragile and decaying agro-economic system, or …a transitioning economy with the [increasing] capacity to eradicate disease”. He questions how the value of different parameters are established and writes that models “do a poor job at dealing with distributional issues (who will be affected and how much)”.

The issue of GCMs has particular resonance with stories in the UK media at the moment. On return from holiday, Tony Blair was asked, and refused, to give up his holiday flights ‘to the sun’ for the sake of reduced carbon outputs – subsequently he was reported to have off-set his carbon through tree planting. I was reminded of the thesis of Shackley et al. (1998) that GCMs lend unconscious support for technocratic and instrumental management responses to climate change. This does little to challenge root causes and inequities in consumption of the world resources. A de-centring of GCMs as the ‘reality of global warming’ and consideration of other forms of evidence, might help to re-imagine and ultimately re-engineer social relations under-pinning climate change. Unsurprisingly, in discussion we were left with many questions as to what this might look like and how it could be achieved.

Friday, January 12, 2007

Happenings at Nottingham

Monday, January 01, 2007

Update from ASU

The ASU crowd has been out of commission lately, but we will hopefully be posting more frequently in the coming months. A few things to report:

My earlier post about modeling at the margin has been adapted and slightly expanded for the newsletter put out by the Center for Science and Technology Policy Research (here). There was some lively discussion about this, including some commentary by climate modeler Richard Tol, over on Roger Pielke's blog.

In the coming months, what you might call the "core" of the ASU modeling group will be buckling down on a little project to explore the issue of "robustness" in greater depth. More on the reading, thinking and discussion that led us to this project soon.

The call for papers for next year's 4S meeting is already available, and is focused on "Ways of Knowing." Of course modeling (however you define it), might fit very well into this theme - stay tuned for panel ideas, or chime in with one here!

Monday, November 27, 2006

Brigitte Nerlich: Media, Metaphors and Modelling

'Media, Metaphors and Modelling: How the UK newspapers reported the epidemiological modelling controversy during the 2001 foot and mouth outbreak'. Forthcoming in: Science, Technology & Human Values

Dr. Brigitte Nerlich

Institute for the Study of Genetics, Biorisks and Society

Law and Social Sciences Building, West Wing

University Park

University of Nottingham

Nottingham NG7 2RD

UK

Daniela M. Bailer-Jones: Scientists' Thoughts on Scientific Models

Further details of Daniela M. Bailer-Jones' work can be found here and here. I am sorry to hear she has passed away. Her work is interesting.

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

Modeling the Margin

Take malaria (please!). The links between climate and malaria are well established. Basically, the temperature of the environment influences the time it takes for the malaria-causing Plasmodium parasite to develop in the gut of the vector mosquito before becoming infectious. This simple relationship can be used to calculate a marginal change in the number of malaria deaths when the average temperature rises by one degree all other things being equal.

But of course, we know that all things will not be equal. Many social, political and cultural factors will come into play. Malaria epidemiology may be related in part to climate, but the amount of suffering and death due to malaria ultimately may have nothing to do with that particular driver. The absence of malaria in the southern United States, where environmental conditions are conducive to the disease, is due to effective health and other infrastructures that render the problem insignificant.

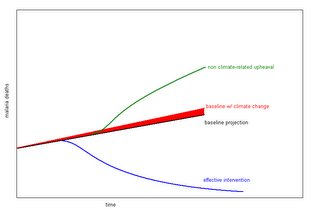

With that in mind, consider this crude, hypothetical, figure showing malaria deaths over time in a developing country:

The red wedge represents the marginal increase in deaths that a climate model might tell us to expect, all other things being equal. But the baseline projection is actually quite unlikely, especially in the context of an unstable government, a fragile and decaying agro-economical system or, conversely, a transitioning economy. Whether the problem is largely solved by effective intervention, or greatly exacerbated by non climate-related disasters like a civil war, overpopulation or some other collapse, the marginal change due to climate seems less important. Even if the baseline proves relatively accurate, the marginal increase due to climate change seems to pale in comparison to the massive failure of efforts to intervene in an eminently solvable problem that causes 8 millions deaths a year.

The red wedge represents the marginal increase in deaths that a climate model might tell us to expect, all other things being equal. But the baseline projection is actually quite unlikely, especially in the context of an unstable government, a fragile and decaying agro-economical system or, conversely, a transitioning economy. Whether the problem is largely solved by effective intervention, or greatly exacerbated by non climate-related disasters like a civil war, overpopulation or some other collapse, the marginal change due to climate seems less important. Even if the baseline proves relatively accurate, the marginal increase due to climate change seems to pale in comparison to the massive failure of efforts to intervene in an eminently solvable problem that causes 8 millions deaths a year.A similar (far more rigorous) argument has been made by Roger Pielke, Jr. and Bobbie Klein (here) with regard to hurricane impacts, and their NSF funded SPARC project seeks to apply this sort of sensitivity analysis to other systems.

But none of this is to say that climate change will be unimportant; of course there may be huge potential consequences for socio-ecological systems at many different scales. Instead I want use this discussion to make a few points/suggestions:

The first is that climate change will likely prove unimportant to many of the problems identified by global models as being impacted by climate change. Society is too complex for us to create a global model of its dynamics (recall Limits to Growth). Instead modelers are left with those variables that can be defensibly and quantifiably linked to climate, while taking into account a handful of currently identifiable global trends (like population growth and urbanization). But these variables are selected without consideration for other drivers that are completely unrelated to climate change - drivers that may prove far more important than a change in average temperature of a few degrees.

For the same reason, a global model of impacts, beyond the inherent and insurmountable uncertainty in what it does predict, has little chance of telling us what the most important problems will be. In other words, the simplest relationships between climate and society (like malaria and temperature) are not necessarily the most important ones. Multiple feedbacks through technology, politics, culture, and environmental dynamics will eventually reveal what our models could not.

Finally, global models of impacts give top-down accounts of how society will be affected by climate change. As such, they do a poor job at dealing with distributional issues (who will be affected and how much), and local dynamics. For example, an impacts model might show that crop yield will be affected in certain regions with certain types of agriculture, and extrapolate this to an economic impact based on some assumed relationship between crop yield and farmer income. But in some communities this might be irrelevant - insurance covers any shortfall, and in any case it is merely a competitive edge that is important, not the aggregate yield. In one local study, it was found that the biggest uncertainty and risk for farmers, even in the face of climate change, was tractor maintenance. Of course it is very important to try to understand how farmers might be impacted by climate change, but what makes us think we can do this with a global model?

What is the alternative to global modeling of climate impacts? Two ideas come to mind:

1. The a priori assumption that global climate change is the only global change problem we need to deal with may not be useful. If one feels the need to frame problems in global terms, climate should be just one of many issues that will be important in shaping the future of humans on Earth. Starting with climate change as a problem, and then building a model around variables that can be plausibly linked to climate change, will of course yield a system in which climate change is the dominant driver or stressor. But the perspective of global change may provide a far more useful (and balanced) context for global problems like climate change.

2. Building on the third point (above), a bottom up approach to identifying and quantifying impacts is crucial to understanding the importance of climate change in socio-ecological systems. The marginal social cost of one ton of carbon emitted into the atmosphere (a number actively debated among envrionmental economists) is no more useful to the rural farmer in zimbabwe than the knowledge that the global average temperature might rise by a few degrees. Local dynamics must be incorporated into any realistic and usable account of climate impacts.

Watching old science fiction movies can often tell us more about the time in which they were filmed than they can about the future. And so it may be with economic models of climate change. These incredibly complex tools strive to show us what the problems will be, based on the problems of today. They identify what we should worry about now, so that tomorrow will be better. But in the end we may better serve future generations by focusing on the problems we know we have now, leaving them better equipped to deal with the problems we could never have predicted.

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

Homo Economicus or Homo ... bounded rationality?

Camerer, C. F., and E. Fehr. 2006. When does "economic man" dominate social behavior? Science 311:47-52.

It has become quite trendy in some circles to reject economics for its adherence to the quaint and seriously flawed idea of "economic man," the rational utility maximizer, hell-bent on material, quantifiable gain. Well, last week the MRG read yet another paper - this one by Camerer and Fehr - that takes up this discussion. But I think we agree that this one brings some quite valuable nuance to the topic of human decision making, or "models of man," in both theoretical and practical terms.

I should say that I forced this somewhat mathy piece on my colleagues because it ties together a few major ideas that have tormented me of late:

- rational decision making,

- game theory, and

- bounded rationality

This is where the Camerer and Fehr paper comes in. They add two concepts to this list that were new to me: strategic complementarity and strategic substitutability. The analogy here is to substitutable or complementary goods, the latter being mutually reinforcing, and the former in opposition to one another. The authors show with both experimental and real-world examples that an understanding of whether strategic complementarity or substitutability is at play can be very useful in determining whether a rational model is appropriate, or whether "boundedly-rational" behavior is more likely to explain results.

This is where game theory comes in. My frustration (perhaps due to a very primitive understanding) with game theory has been what seems like an effort to generalize, at some level, the primary motivating factors that can explain human behavior in particular decision making environments. The beauty of this paper is that this endeavour can be brushed aside. Instead, the authors accept that in any situation you may have unexplainable behavior that might be rational or boundedly rational. What is more important is to understand that in some situations (strategic substitutability) the rational behavoir is dominant in determining the outcomes, thus rendering boundedly rational actors irrelevant. In situations of strategic complementarity the situation is reversed.

Of course we would lose all credibility if this blog entry was a totally reverent of the piece without some brilliantly cogent criticsim. We noted that the definition of rationality becomes a bit problematic in some of the cases presented in this article, especially once the discussion shifts to questions of strategy. For example, it is noted that in some games, the presence of boundedly rational players causes more rational players to mimic that behavior. But at this point, the decision to adopt boundedly rational behavior actually appears to be rational, at least in terms of our expectations of utility maximization. So, while behavior is homogenous, some players are genuinely boundedly rational, while others are simply acting that way to maximize their utility, but it is impossible to tell which players are which.

Our question is: in this context, what would constitute rationality? It seems that now the term refers only to what is classically expected in situations with all rational players, rather than to our more traditional notion of maximization. It would help to clarify this once the discussion gets into these complicated situations in which rational players adapt their behavior to to presence of boundedly rational players.

That aside, perhaps the most important recognition here, with respect to neoclassical economics, is that aggregate behavior does not reflect homogenous behavior or even homogenous motivations. In some situations the homo economicus model fails to predict aggregate outcomes, and in others it does not. But in neither case does it provide an accurate account of individual decision making.

Monday, October 02, 2006

Forecast discussion on Prometheus

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

The Wrongness or Rightness of Models: (Or, “if this model is wrong, then I just don’t wanna be right!)

The ASU MRG (Modeling Reading Group) held its second meeting last Friday to discuss a book chapter by Naomi Oreskes and Kenneth Belitz called “Philosophical Issues in Model Assessment” (in Model Validation: Perspectives in Hydrological Science; 2001; M.G. Anderson and P.D. Bates eds.). Though aimed at hydrologists, we found that this article stays true to its title, providing a short and, at times provocative summary of some basic issues that anyone using models might want to think about. Topics range from philosophy and logic to political, cultural, and social issues that might be important in thinking about how we represent natural processes in simplified models.

The big thesis underlying the piece is that we (scientists? ...they seem to put the onus on scientists…) should not appeal to models for any sort of prediction about the world. Rather, “one can gain insight and test intuitions through modeling without making predictions. One can use models to help identify questions that have scientific answers.”

Why shouldn’t we use models to predict? First, and, perhaps the most important, is the logical impossibility of model validation. There are a number of potential reasons for this, like non-uniqueness (the fact that more than one model may give the same result), compensating errors (errors that cancel each other out within certain conditions), or the difficulty of estimating unlikely events. In other words, even when we have observational data with which to compare a model, we have no way to prove that the underlying causal structure leading to what we observe is the same as that leading to our model result.

In addition, the authors cite a number of practical reasons that models may prove unhelpful when used to predict, such as the common “illusion of validity,” in which something is accepted as truth merely because it works, or the cultural and political pressure to predict the “right” outcome, or temporal and spatial divergence in which the future may be quite different from the historical data used to “validate” a model.

In general, I think our group found the concepts pertaining to model validity to be fairly straightforward.

Model Wrongness

Our most spirited discussion centered around what we saw as an inconsistency in the authors’ interpretations of examples they presented to demonstrate the difficulty of model validation. If a model predicts a certain outcome based on continued trends, and as result human behavior changes, was that model wrong? Indeed, was its use at all inappropriate?

The authors would have us believe that yes, the model was incorrect and, no, it should not have been used. But here is where we think Oreskes and Belitz fall into their own trap: just as it would be impossible to tell if the model in question is correct, it is also impossible to tell if it is wrong – especially if the model result itself induces a change in (human) behavior feeding back into the very system being modeled.

What is missing in all this talk about model validation is a discussion and characterization of model “wrongness,” (perhaps this would resemble the many layers of uncertainty in a model). It is perfectly plausible (though unknowable) that the model of groundwater levels captured physical processes accurately. It was wrong about human behavior, but then again, this was precisely the point – to understand the consequences of a sustained human behavior.

This is not to argue against the main conclusions of the chapter, with which I believe we all agreed, but merely to point out that to discuss models in terms of being “wrong” misses the point of the chapter’s more nuanced conclusion that models can be useful but dangerous tools precisely because we cannot know if they are right or wrong. The water model examples suggest that there can be an excruciatingly fine line between using models to “gain insight and test intuitions” (as the authors advocate) and predicting the future.

A few other ideas and issues that came of our discussion:

Oreskes and Belitz make the interesting argument in the section on systematic bias that models will tend to be optimistic. They note that very rare events are almost impossible to describe in terms of their probability and may even be unknowable. The logic, then, is that “in highly structured, settled human societies, unanticipated events are almost always costly…” and thus the optimistic bias. We felt this was an interesting point, which must certainly be valid in many cases, but that it should probably not be generalized. We see even from the examples in the chapter that models can be quite pessimistic, especially when modelers are worried that a behavior change is needed. It is important to recognize that models have a social dimension to them – they are tools used to reveal certain types of information in certain ways. So, yes, models (especially long term ones) may miss major unpredictable events, but they may also be structured to yield doom and gloom scenarios that direct human behavior.

The authors touch on this when they mention that part of modeling successfully may involve the production of results that are pleasing to a modeler’s constituents. This certainly seems plausible in the case of the modeler concerned about dropping groundwater levels. Can we think of models as just a set of goals? Matt suggested that a starting point for this line of thinking might be the example of an entrepreneur developing a five year business model. In terms of goals or desired outcomes, how is this similar or different from modeling the water table?

Finally, picking up again on the idea of model wrongness, what are the implications of taking one’s model to a policy maker? I ask this because, in my mind, it may actually change the model itself. By using a model to inform policy, are we by definition forcing social dynamics into a numerical model that had previously been concerned only with water flow (for example)?

There are many other appetizing tidbits in this chapter that would generate an interesting discussion (perhaps a comment from Zach, and maybe even the authors themselves is forthcoming?), but I will stop here with the final recommendation that this chapter is a great starting point for anyone looking to sink their teeth into some of the fleshier, juicier issues in models for both natural and social sciences. Enjoy!

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Models of the world...

"It is impossible to begin any human activity without models of the world."

The context here was a brief discussion of a particular reference, but the implications are obviously much broader. If we accept this idea, then of course the question of whether or not models are appropriate for use in problem solving no longer makes any sense. Instead, the interesting questions are which models, and why? It also forces us to recognize that any information should be regarded as resulting from some model of the world that is purely socially constructed.

The article begins with an account of C. S. Hollings "two streams of science": the mainstream experimental and reductionist; and the lesser known (but growing in popularity?) interdisciplinary, integrative etc. The dominance of the former as a mental model for how knowledge should be generated has of course been extremely important to scholarship, politics, policy making, and decision making in general. Perhaps we are beginning to see a shift toward the latter, which not only brings about new frameworks for addressing problems, but gives new life to disciplines (like anthropology, the author argues), that already have extensive experience in this realm.

Tuesday, August 08, 2006

Models of society and citizenship

Selection criteria for universities is an interesting case. See this book review in the Economist which finishes with the provocative (?) conclusion "the ideal of a meritocracy ... is inherently unattainable" (thanks to Peter Danielson for drawing my attention to it).

Monday, August 07, 2006

Towards a sociology of modelling

Sunday, July 30, 2006

Welcome

- What can models tell us about the world today?

- What can models tell us about the future?

- When are models most useful?

- Under which conditions is complexity or simplicity most appropriate?

- How can we understand various forms of uncertainty in models?

- When can models play a useful role in decision making?

- What can we learn from the varying approaches to modeling in different disciplines and research areas?