Take malaria (please!). The links between climate and malaria are well established. Basically, the temperature of the environment influences the time it takes for the malaria-causing Plasmodium parasite to develop in the gut of the vector mosquito before becoming infectious. This simple relationship can be used to calculate a marginal change in the number of malaria deaths when the average temperature rises by one degree all other things being equal.

But of course, we know that all things will not be equal. Many social, political and cultural factors will come into play. Malaria epidemiology may be related in part to climate, but the amount of suffering and death due to malaria ultimately may have nothing to do with that particular driver. The absence of malaria in the southern United States, where environmental conditions are conducive to the disease, is due to effective health and other infrastructures that render the problem insignificant.

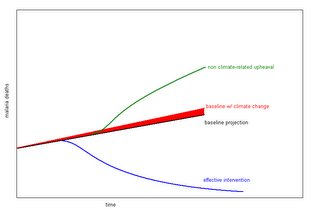

With that in mind, consider this crude, hypothetical, figure showing malaria deaths over time in a developing country:

The red wedge represents the marginal increase in deaths that a climate model might tell us to expect, all other things being equal. But the baseline projection is actually quite unlikely, especially in the context of an unstable government, a fragile and decaying agro-economical system or, conversely, a transitioning economy. Whether the problem is largely solved by effective intervention, or greatly exacerbated by non climate-related disasters like a civil war, overpopulation or some other collapse, the marginal change due to climate seems less important. Even if the baseline proves relatively accurate, the marginal increase due to climate change seems to pale in comparison to the massive failure of efforts to intervene in an eminently solvable problem that causes 8 millions deaths a year.

The red wedge represents the marginal increase in deaths that a climate model might tell us to expect, all other things being equal. But the baseline projection is actually quite unlikely, especially in the context of an unstable government, a fragile and decaying agro-economical system or, conversely, a transitioning economy. Whether the problem is largely solved by effective intervention, or greatly exacerbated by non climate-related disasters like a civil war, overpopulation or some other collapse, the marginal change due to climate seems less important. Even if the baseline proves relatively accurate, the marginal increase due to climate change seems to pale in comparison to the massive failure of efforts to intervene in an eminently solvable problem that causes 8 millions deaths a year.A similar (far more rigorous) argument has been made by Roger Pielke, Jr. and Bobbie Klein (here) with regard to hurricane impacts, and their NSF funded SPARC project seeks to apply this sort of sensitivity analysis to other systems.

But none of this is to say that climate change will be unimportant; of course there may be huge potential consequences for socio-ecological systems at many different scales. Instead I want use this discussion to make a few points/suggestions:

The first is that climate change will likely prove unimportant to many of the problems identified by global models as being impacted by climate change. Society is too complex for us to create a global model of its dynamics (recall Limits to Growth). Instead modelers are left with those variables that can be defensibly and quantifiably linked to climate, while taking into account a handful of currently identifiable global trends (like population growth and urbanization). But these variables are selected without consideration for other drivers that are completely unrelated to climate change - drivers that may prove far more important than a change in average temperature of a few degrees.

For the same reason, a global model of impacts, beyond the inherent and insurmountable uncertainty in what it does predict, has little chance of telling us what the most important problems will be. In other words, the simplest relationships between climate and society (like malaria and temperature) are not necessarily the most important ones. Multiple feedbacks through technology, politics, culture, and environmental dynamics will eventually reveal what our models could not.

Finally, global models of impacts give top-down accounts of how society will be affected by climate change. As such, they do a poor job at dealing with distributional issues (who will be affected and how much), and local dynamics. For example, an impacts model might show that crop yield will be affected in certain regions with certain types of agriculture, and extrapolate this to an economic impact based on some assumed relationship between crop yield and farmer income. But in some communities this might be irrelevant - insurance covers any shortfall, and in any case it is merely a competitive edge that is important, not the aggregate yield. In one local study, it was found that the biggest uncertainty and risk for farmers, even in the face of climate change, was tractor maintenance. Of course it is very important to try to understand how farmers might be impacted by climate change, but what makes us think we can do this with a global model?

What is the alternative to global modeling of climate impacts? Two ideas come to mind:

1. The a priori assumption that global climate change is the only global change problem we need to deal with may not be useful. If one feels the need to frame problems in global terms, climate should be just one of many issues that will be important in shaping the future of humans on Earth. Starting with climate change as a problem, and then building a model around variables that can be plausibly linked to climate change, will of course yield a system in which climate change is the dominant driver or stressor. But the perspective of global change may provide a far more useful (and balanced) context for global problems like climate change.

2. Building on the third point (above), a bottom up approach to identifying and quantifying impacts is crucial to understanding the importance of climate change in socio-ecological systems. The marginal social cost of one ton of carbon emitted into the atmosphere (a number actively debated among envrionmental economists) is no more useful to the rural farmer in zimbabwe than the knowledge that the global average temperature might rise by a few degrees. Local dynamics must be incorporated into any realistic and usable account of climate impacts.

Watching old science fiction movies can often tell us more about the time in which they were filmed than they can about the future. And so it may be with economic models of climate change. These incredibly complex tools strive to show us what the problems will be, based on the problems of today. They identify what we should worry about now, so that tomorrow will be better. But in the end we may better serve future generations by focusing on the problems we know we have now, leaving them better equipped to deal with the problems we could never have predicted.

1 comment:

needless to say, I am highly sympathetic with this perspective. There's an additional element here that's even more infuriating (if that's possible): for all the posturing about the (unpredictable) marginal impacts of climate change, presumably the implication is supposed to be that we need to reduce carbon emissions to prevent more malaria, storm damage, agricultural dislocation, etc. etc. But if predicting the marginal effects of climate change is impossible, for reasons Ryan outlines, how much more absurd is it to think we can say anything remotely plausible about the effects of some marginal level of emissions reductions (compared to what??!!) in ameliorating those marginal impacts?

Post a Comment